The Most Unsettling Archaeological Sites

Oct 27, 2025

By: Greg Schmalzel

I love archaeology because it’s not just about objects. It’s about people and the world we once experienced. Sometimes it reveals a beautiful world that ancient artists left behind, but it often elicits fear in the eyes of archaeologists themselves. A plastered skull with shells for eyes. A child frozen in ice. A body curled in a bog with a noose still tight around his neck. These finds feel personal, almost too personal. They’re moments when the past looks back at us with traces of fear, ritual, and an unsettled stomach. And they leave questions we can’t shake. Who were these people and why did their lives end? What was it like to be them just moments before they were laid to rest? So stick around, because these are some of the most unsettling archaeological sites ever uncovered and their stories won’t leave your mind.

For the full YouTube video, click HERE.

The Taung Child and Predatory Birds

Ettore Mazza

The story begins in Taung, a small town in South Africa. In 1924, limestone quarry workers uncovered something extraordinary — a fossilized skull buried 25 feet below ground. Professor Raymond Dart identified it as Australopithecus africanus, an early human ancestor nearly 3 million years old. Known today as the Taung Child, it belonged to a child about three or four years old and became one of the most important discoveries in the study of human evolution. The skull displayed both ape-like and human-like traits, revealing a key step toward upright walking. But what makes this fossil truly haunting isn’t just who the child was — it’s how it died.

Closer examination revealed small punctures and scratches near the eyes. These weren’t tool marks or signs of a fall. For years, scientists thought the child had been killed by a large cat. But in 1995, researchers Lee Berger and Ron Clarke proposed something far more chilling — that the Taung Child was snatched and killed by a bird of prey. The wounds matched those seen on monkey skulls attacked by crowned hawk eagles in modern Africa.

If that’s true, the Taung Child represents one of the earliest known examples of a human ancestor being hunted from above. It’s a sobering reminder that in our deep past, humans were not always the predators — we were sometimes the prey. And in this case, the deadliest hunter wasn’t on the ground, but in the sky.

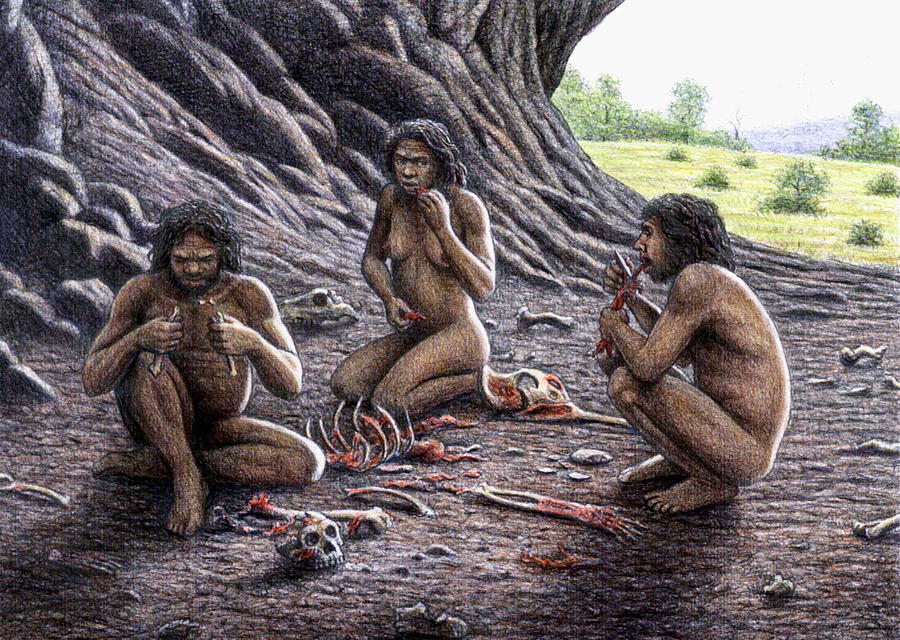

Cannibalism in Homo Antecessor

Humans weren’t always victims of nature — sometimes, the danger came from each other. Nearly a million years ago in Spain’s Atapuerca caves, Homo antecessor lived — an early human species with surprisingly modern faces. In a cave called Gran Dolina, archaeologists uncovered thousands of bones, many scarred with cut marks and fractures identical to those found on butchered animals.

Around 40% of the human remains showed evidence of cannibalism — not from desperation, but repeated, organized violence. Most victims were children. Like chimpanzee raids today, these attacks targeted the weak. Europe’s story, it seems, began with humans turning on their own kind.

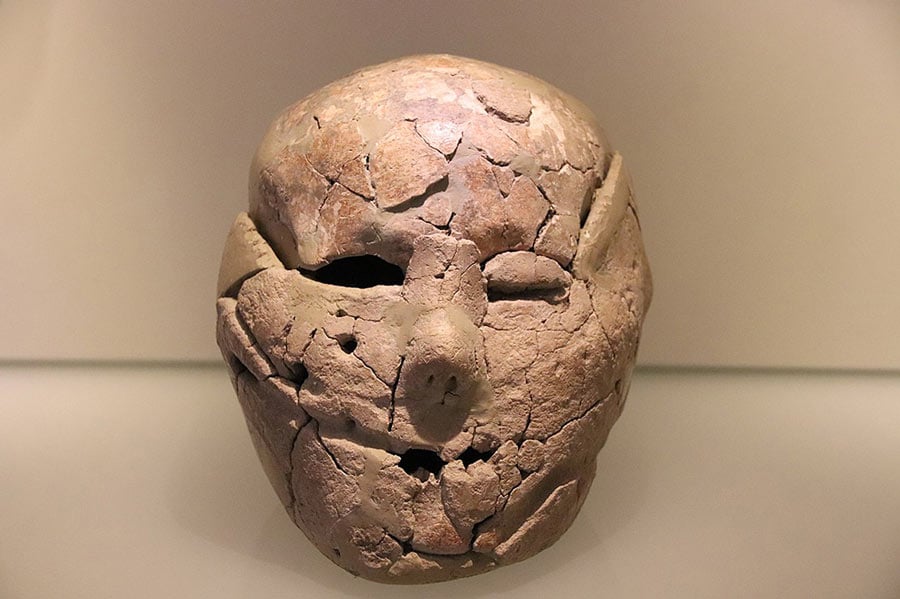

The Skulls of Jericho

Jericho, one of the world’s oldest cities, shows that unsettling archaeology isn’t limited to primitive species. Twelve thousand years ago, early Homo sapiens camped here — fully modern humans who soon transitioned into farming, building mud-brick homes, and even constructing massive stone walls and a tower around 8300 BCE. But inside those homes, archaeologists uncovered something far more intimate and eerie: plastered skulls.

These weren’t trophies or public displays. They were household relics. Craftsmen took cleaned skulls, filled the eye sockets and mouth with ochre plaster, smoothed fine layers over the face, and sometimes pressed seashells in for eyes. The result is haunting — faces that seem to stare back across 10,000 years. Most were found beneath floors or hidden in debris, suggesting they were kept as personal keepsakes, perhaps to honor ancestors or preserve the memory of loved ones.

To modern eyes, they look terrifying — ghostly remnants of the dead. But to the people of Jericho, they were probably acts of love, attempts to keep their family close after death. The plastered skulls blur the line between life and remembrance. They’re unsettling not because they’re monstrous, but because they’re so deeply human — both eerie and profoundly tender.

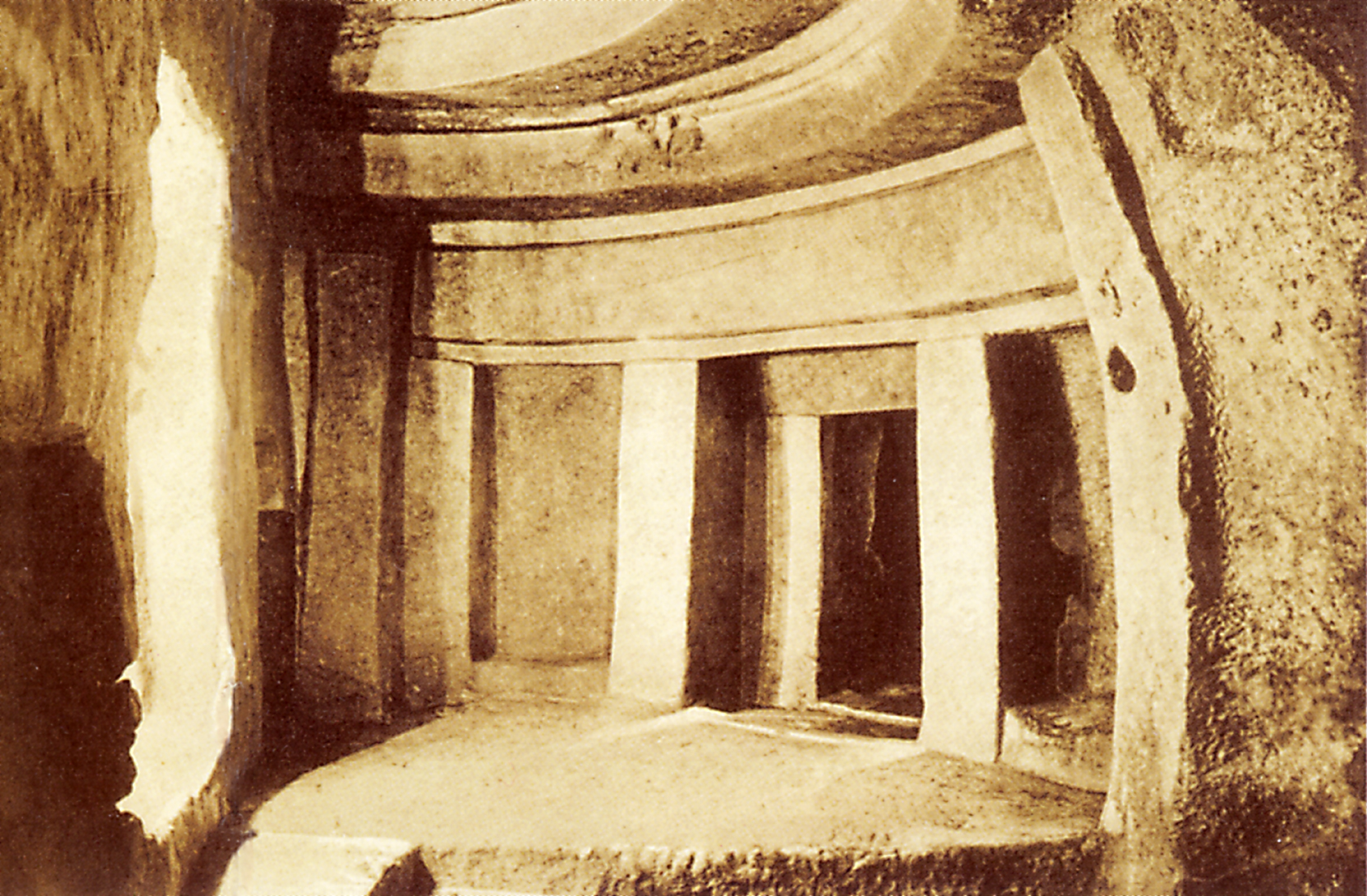

The Ħal-Saflieni Hypogeum in Malta

Beneath the modern town of Paola, Malta, lies one of the strangest sites in the Mediterranean — the Ħal-Saflieni Hypogeum. Carved into limestone around 4000 BCE, this underground labyrinth served as both a necropolis and a ritual center. It was discovered by accident in 1902, when construction workers broke through the ceiling of its upper chamber and found bones and pottery. Excavations led by Themistocles Zammit revealed three carved levels filled with chambers, ochre-painted walls, and eerie acoustics.

The middle level is the most elaborate, featuring trilithon doorways, spiral motifs, and the small Oracle Room, which echoes human voices in haunting ways. The famous Sleeping Lady figurine — depicting a woman resting on her side — was found here too. Thousands of skeletons once rested within, many coated in red ochre and reburied over generations. Archaeologists describe it as a collective tomb and a sacred space where sound, light, and death intertwined.

By 2500 BCE, the Hypogeum was abandoned, likely due to environmental stress — eroded soil, dwindling wood, and disease. But the site remains chilling. Underground. Silent. Claustrophobic. It’s a place where architecture, art, and ritual fused into a single meditation on mortality — a Stone Age cathedral to the dead.