Homo Erectus: The First Humans to Leave Africa

Jan 20, 2025

By: Greg Schmalzel

Two million years ago, a group of humans stood up, left Africa, and changed the course of humanity forever. A population, once constrained to the confines of one continent, made their way east, toward new and unpredictable environments. This was a group of what we now call Homo erectus.

Homo erectus is known for many things. Anthropologists often consider it the first “upright man” or the first “truly human species” more generally. It is also arguably the most successful human species, having existed for approximately 2 million years. It is all of these things, but it also holds the title as the first human species to leave Africa.

But, why this species and not the earlier Homo habilis or even earlier yet Australopithecines? The human lineage had been evolving in Africa since roughly 7 million years ago. So, why wasn’t it until Homo erectus that new territories were explored? Today, we’ll be answering these questions and uncovering the secrets that set Homo erectus apart

We’ll discover what made Homo erectus so special: specifically, its suite of physical, cognitive, and social adaptations that allowed it to make such long journeys away from home.

Who were these ancient explorers? How did they conquer vast distances? And what became of them as they ventured into the farthest reaches of the ancient world?

Let’s find out.

Watch the video version here.

Who was Homo erectus?

Geographic distribution of Homo erectus.

In 1891, Eugene Dubois, a Dutch physician turned paleoanthropologist, made a groundbreaking discovery in Indonesia. Influenced by German evolutionary biologist Ernst Haeckel’s theory that humanity originated in Asia, Dubois sought the elusive “ape-man” Haeckel had already named Pithecanthropus. This belief stemmed from perceived anatomical similarities between humans and orangutans.

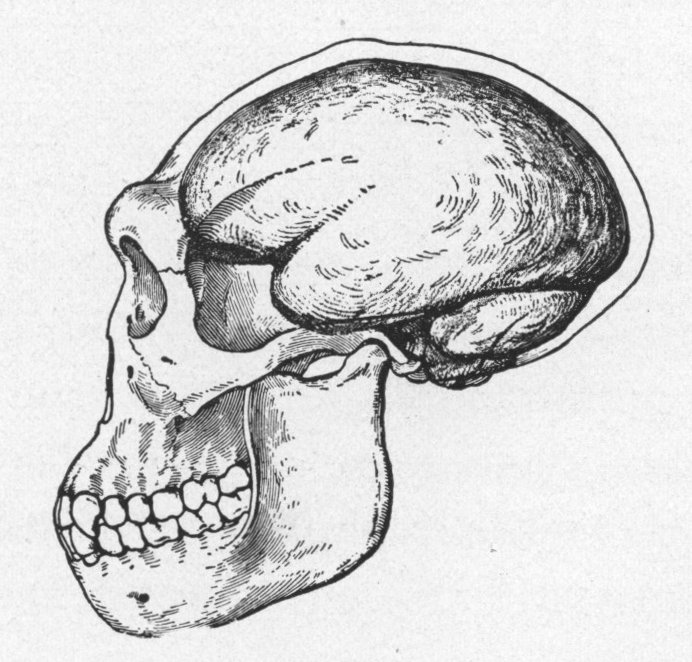

Initially unsuccessful in Sumatra, Dubois shifted to Java, where bones were reportedly eroding out of the Solo River near Trinil. Excavations revealed a human molar, a skull fragment, and a femur. The skull, with its pronounced brow ridge, was unlike modern humans but larger than any non-human primate. Dubois named the specimen Pithecanthropus erectus, later nicknamed "Java Man." It marked the first discovery of Homo erectus and, at the time, the oldest known human bones.

While significant, the discovery's initial conclusion that humanity originated in Asia did not hold up. Figures like Charles Darwin had proposed Africa as the cradle of humanity, citing the close relationships between living African apes and humans. Excavations in Africa—at sites like Olduvai Gorge and Lake Turkana—uncovered older Homo erectus fossils and even earlier species like Homo habilis and Australopithecines, solidifying Africa’s primacy in human evolution.

Despite its African origins, Homo erectus is unique for its broad distribution. Fossils have been found in regions as diverse as Turkey, China, Georgia, and Germany, with “Java Man” being just one example. This wide range reflects Homo erectus' adaptability and success across varied environments. This geographic diversity led to physical variations among Homo erectus populations. Some anthropologists classify these as subspecies—e.g., Homo erectus ergaster, H. e. georgicus, and H. e. soloensis—while others view them as regional adaptations within a single species.

Despite these differences, common traits unite Homo erectus as a distinct human species, bridging the gap between earlier hominins and modern humans. These defining traits, their role in the species’ dispersal, and their legacy in Homo sapiens will be explored in the next sections.

Physical Adaptations

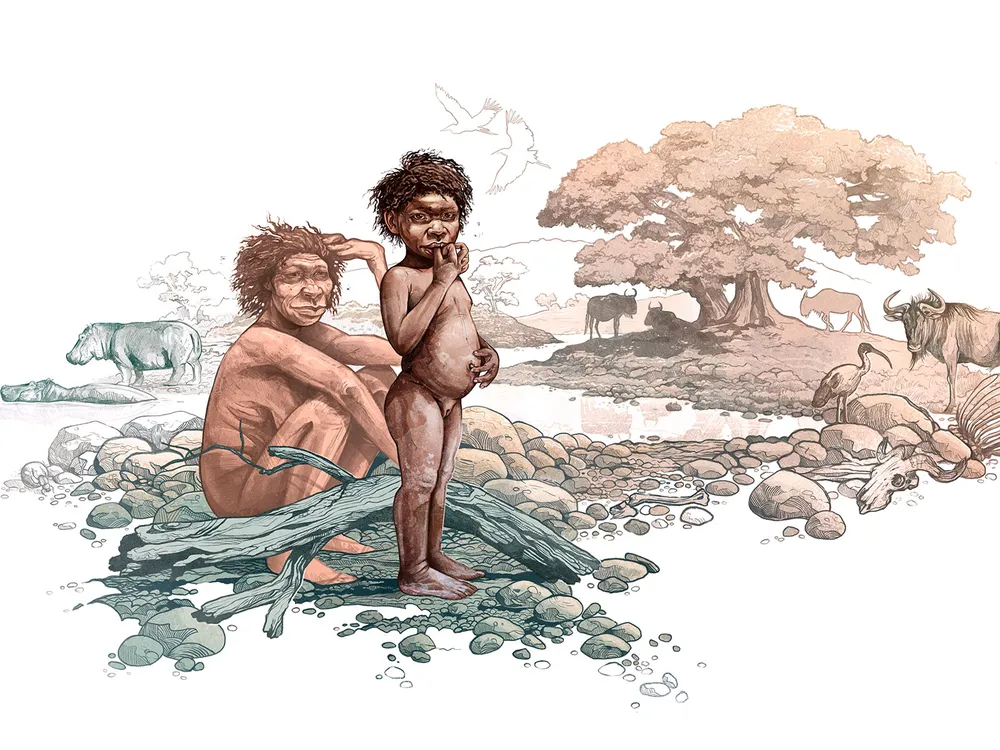

Illustration of Homo erectus by Mauricio Anton.

Humans engaging in extreme physical activity for non-survival reasons is a curious anomaly in nature. Homo erectus, however, relied on endurance for survival and migration, a trait evident in their physical and behavioral adaptations.

The body plan of Homo erectus was uniquely suited for long-distance travel. Unlike earlier hominins, they had longer legs than arms, a taller stature (averaging about 5’9”), and an overall physique adapted to efficient bipedal locomotion. These traits enabled them to cover significant distances with less energy, a crucial advantage when moving between distant water sources or hunting grounds. Fossilized footprints from Ileret, Kenya, dating back 1.5 million years, further support these findings. These prints reveal modern-like weight transfer, arched feet for energy-saving strides, and big toes aligned for balance and stability, highlighting their advanced adaptation to life on the ground.

Physiological adaptations played an equally critical role in enabling endurance. Features such as reduced body hair, increased sweat glands, and mouth breathing allowed Homo erectus to dissipate heat effectively during sustained exertion, reducing the risk of overheating. Though physical evidence of these traits is lacking, studies suggest that these adaptations allowed them to run for extended periods, with one estimate indicating they could run up to 5.5 hours before dehydration.

One of the most remarkable behaviors associated with Homo erectus is persistence hunting. This strategy involved running prey to exhaustion, leveraging endurance rather than speed. While prey animals were faster in short bursts, the sustained effort of Homo erectus outlasted their quarry, a method still practiced by some modern hunter-gatherers. This ability marked a turning point in human evolution, as it provided a reliable means of securing food in challenging environments.

The evolution of endurance in Homo erectus is even more striking when compared to earlier hominins like Australopithecus afarensis. Studies using running simulations for afarensis suggest their speed and endurance were significantly lower, underscoring the specialized adaptations that emerged with Homo erectus.

These physical traits enabled Homo erectus to overcome natural limitations, facilitating their migrations out of Africa and across vast territories. Combined with cognitive and cultural innovations, they laid the foundation for human dominance. In the next section, we explore the cognitive breakthroughs that defined the psyche of Homo erectus.

Cognitive Adaptations

Thoughts don’t fossilize, and neither do brains, but skulls do—and they provide a faint glimpse into the cognitive power of ancient hominins. Over time, the archaeological record reveals a pattern of increasing brain size across human evolution, punctuated by periods of rapid growth. One of these major leaps occurred with Homo erectus.

The cranial capacity of Homo erectus ranged from 725 to 1,125 cubic centimeters (cc), significantly larger than that of its predecessor, Homo habilis (507 to 690 cc). This increase brought brain sizes closer to those of modern humans. However, larger brains came at a cost: longer gestation periods, more difficult childbirths, prolonged infant dependency, and a high metabolic demand. Despite these challenges, evolutionary advantages—likely tied to survival and adaptation—outweighed the costs.

Bigger brains brought increased capacity for advanced thinking. Regions like the prefrontal cortex and neocortex expanded more significantly, enhancing decision-making, problem-solving, social cognition, and creativity. These developments supported innovations like tool use, navigation, and adaptability to diverse environments, paving the way for Homo erectus migrations out of Africa.

Interestingly, dopamine—a neurochemical tied to motivation, reward, and novelty-seeking—may have played a role. Increased meat consumption and physical activity associated with persistence hunting might have amplified dopamine levels, fostering goal-driven behavior and curiosity. This could explain Homo erectus’ motivation to explore uncharted territories.

The evolutionary leap in brain size marked just one facet of Homo erectus’ transformation. Their tools, social structures, and adaptability also played a crucial role in their success—topics explored in the next section. For a deeper dive into the evolution of the human brain, check out my video on the matter here.